The cascading insights behind Meesho’s zero-to-multibillion journey

Meesho built a multi-billion dollar business by breaking every e-commerce rule. Serve unbranded products nobody else wants? Check. Incentivise housewives to become your salesforce instead of owning your own customers? Check. Embrace ₹200 average order values that would bankrupt competitors? Check. Each decision conventional wisdom said would fail became a defensible moat.

This is exactly the type of opportunity we're built to back.

When we invested in Meesho, the business looked incomprehensible to most investors. But we saw something others missed: emergent user behavior that revealed deeper truths about India. Housewives weren't a bug in the system – they were the key to scaling trust in a low-trust economy. Low AOV wasn't a problem to fix – it was a moat competitors couldn't cross. Each "wrong" choice became defensible.

Today, Meesho processes 4.5 million daily orders and serves 213 million annual users (88% from outside India's top eight cities). They're now a public company as you read this.

What follows are six insights Vidit and Sanjeev discovered while building from the ground up. Each one challenged conventional wisdom. Each remained non-consensus for years. Together, they explain not just why Meesho won, but what we look for in every investment: jarring insights that make us see how the world already works in a new light.

–

In 2015, Meesho was born out of an idea-brainstorming process we wouldn’t recommend to anyone: they made a spreadsheet with every popular business model (Airbnb/Uber/hyperlocal for…) in each row and every sector (groceries, travel, e-commerce) across each column.

While they found a lot of players in the row for hyperlocal models and in the column for the fashion sector, they found very few meaningful approaches that addressed the intersection of the two.

And so was born FashNear (“fashion, nearby”), a hyperlocal fashion platform. In Vidit’s words:

It wasn’t the spreadsheet jiu-jitsu, but the next 6 months that really led to Meesho: sitting in local shops, watching how these SME fashion businesses operated, and understanding how they bridged the trust gap with consumers. Over time, this was replicated up the supply chain: from the neighborhood shops, to wholesale traders, to local manufacturers.

Once it was understood that the majority of commerce activity came from small, unbranded businesses (see India is a long-tail economy), the question became: How do you bring India's small businesses online?

Insight 1: The majority of Indian retail is unbranded, and it lacks an online presence

When you walk through a typical Indian bazaar where most Indians shop, you see thousands of products with no brand recognition. These are products from small manufacturers, often family-run businesses that have been making the same items for decades, sold through layers of traders and wholesalers before reaching local shops.

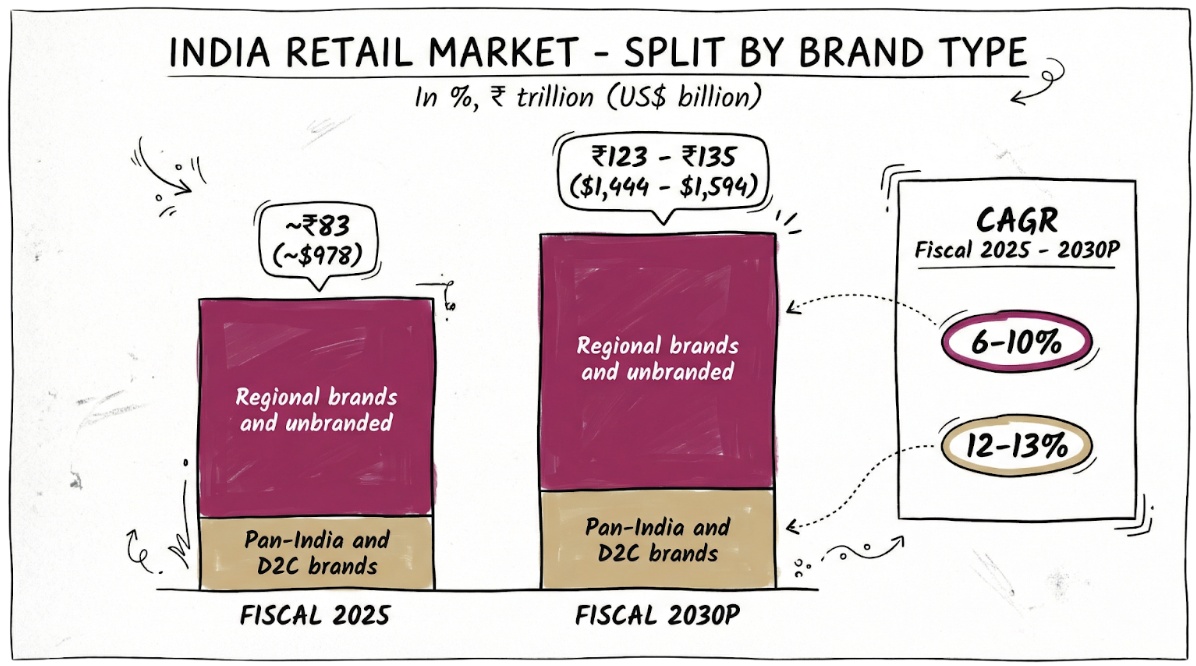

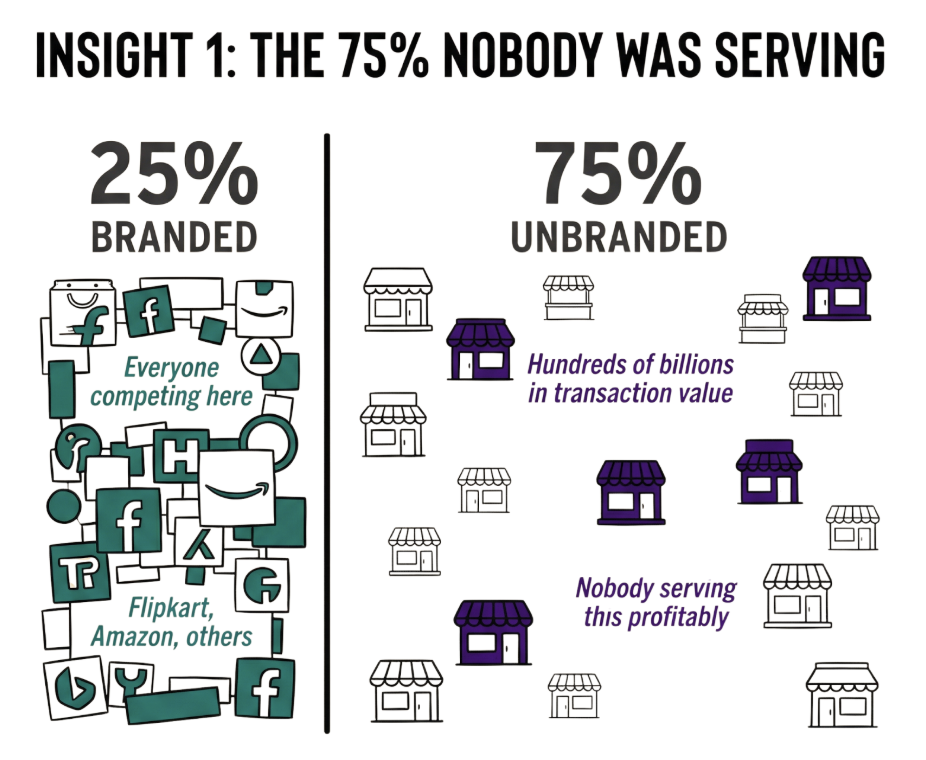

~75% of India's retail is unbranded. Like most industries in India, it’s long-tail dominated.

What Meesho Did: Vidit & Sanjeev first venture, Fashnear, was built specifically for this unbranded retail landscape. The concept was to help local businesses and shops get discovered online. Fashnear would make unbranded fashion products discoverable through hyperlocal search. Users could see shops near them on the app, select products to try at home, and get the convenience of online discovery with the trust of local retail.

It was a smart insight: these small shops would never build their own e-commerce presence, but they could benefit from a platform that brought them online while preserving the local, personal shopping experience their customers valued.

The Lesson: Fashnear's failure revealed something valuable. Every major e-commerce player was competing for the 25% of retail that was consolidating around branded products; nobody was building for the other ~75%. That unbranded majority represented hundreds of billions in annual transaction value and would remain structurally so – shaped by India's regional diversity, low capital, and distributed manufacturing.

By recognising this permanence, Meesho shifted its focus from competing in a crowded space to building for a market nobody else was serving profitably. The question then was: How do unbranded products actually get discovered and purchased in India?

Insight 2: WhatsApp in India is the trust layer.

In India, WhatsApp isn't just a messaging app – it’s our social infrastructure. For small business owners, WhatsApp represents zero customer acquisition cost, zero app download friction, universal penetration across age groups and income levels, built-in social proof through groups, and informal trust networks already established.

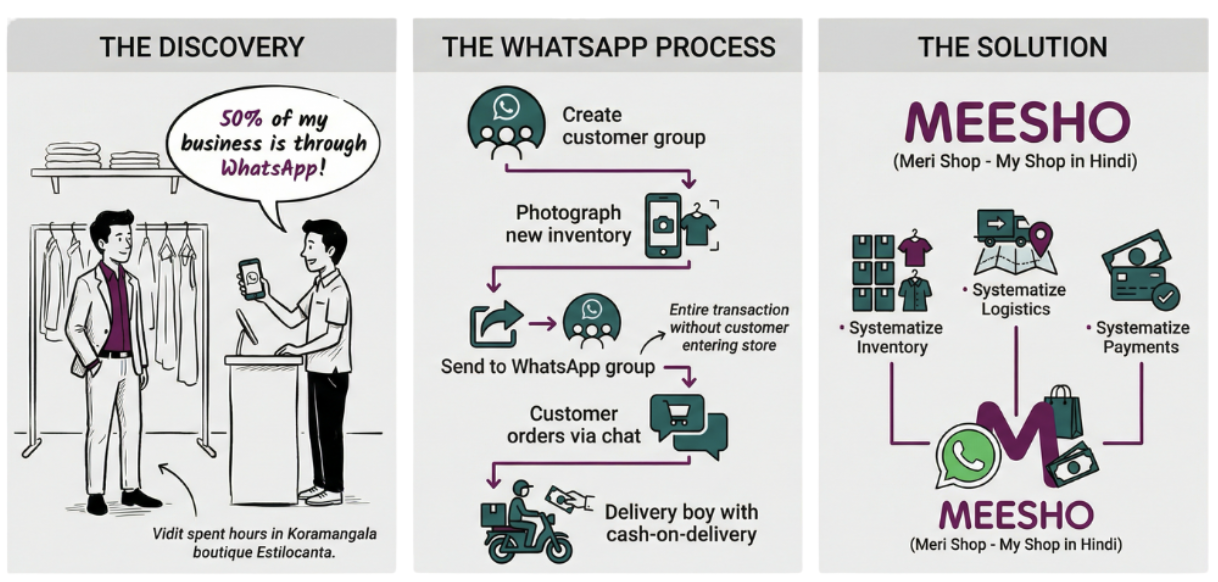

What Meesho Did: Vidit spent hours in a Koramangala boutique called Estilocanta, watching how the business operated. The shopkeeper eventually struck up a conversation and shared something that seemed impossible: he was doing 50% of his business through WhatsApp.

He'd created a WhatsApp group with every customer who walked in. New inventory? Photograph it, send it to the group. Someone wants to buy? Send a delivery boy to their home with cash-on-delivery. The entire transaction happened without the customer entering the store.

From this, Meesho was born (short for "Meri Shop"—My Shop in Hindi). The concept: help SMB owners systematize their WhatsApp commerce—inventory, logistics, payments.

Once they launched, they saw quick growth, but their power users weren't the SMEs they built Meesho for. The unexpected adoption came from homemakers who weren't running traditional shops, but had found a way to become micro-entrepreneurs..

The Lesson: WhatsApp isn’t just a channel – it is entrepreneurial infrastructure. The real opportunity wasn't digitizing existing shops, but discovering who would actually drive distribution through these trust networks.

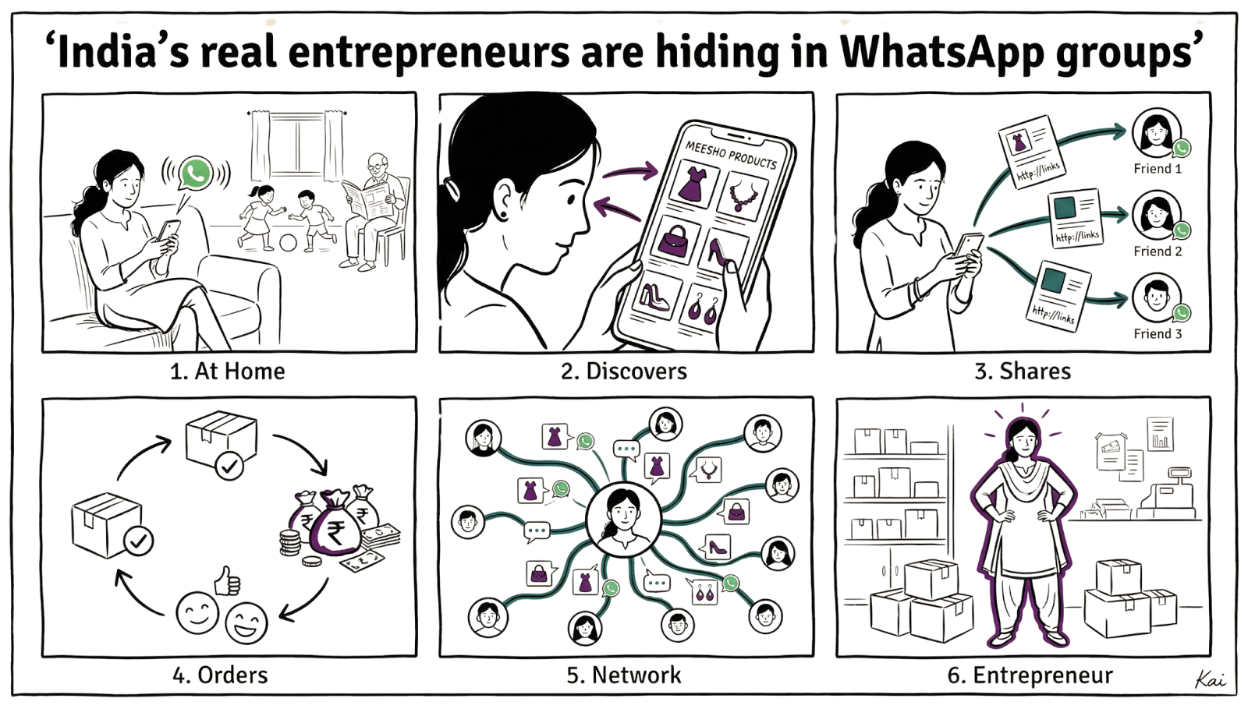

Insight 3: India's real entrepreneurs are hiding in WhatsApp groups

When Vidit looked at Meesho's most engaged users, the pattern was clear but unexpected. These weren't the SMB shop owners he'd built the product for. They were women in Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan - often in Tier 2/3 cities - running what they called "WhatsApp boutiques."

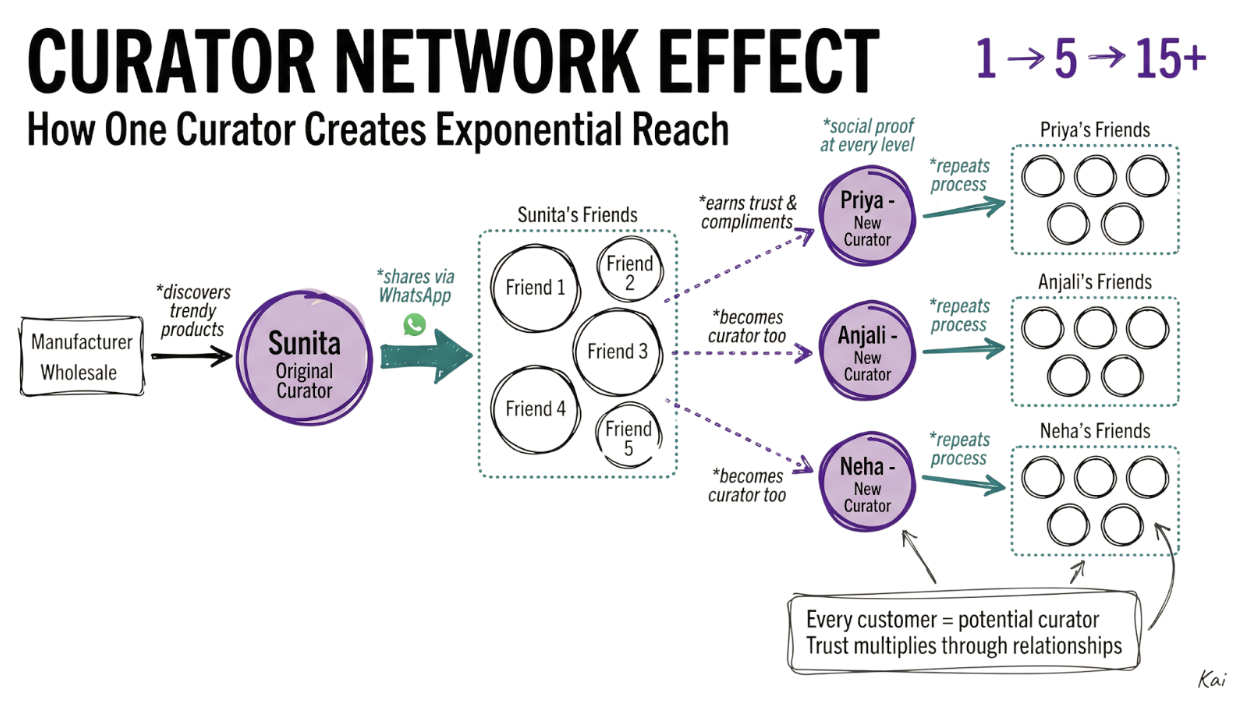

Here's how it worked: Housewives would browse Meesho's catalog, select products they thought their social circles would like, and then share in their WhatsApp groups. When their audience wanted to buy, the housewife would place the order through Meesho, add their 10-20% margin plus shipping, and collect payment on delivery. Pure intermediation — curating supply for demand in their personal networks. Their engagement metrics were dramatically higher than SMB owners.

For a shop owner, Meesho was a side project. For these women, it was everything.

This wasn't an arbitrage to fix, it was the business model. In India's Tier 2/3 cities, millions of women want financial independence but face cultural constraints on traditional employment. So India has always had invisible home businesses: beauty parlors in spare bedrooms, tuition classes for neighborhood kids, tiffin services, tailoring businesses. Women finding ways to earn while staying within social boundaries.

What Meesho discovered was that these women had something more valuable than inventory: trust built over years. Indians don't default to trusting institutions, systems, or brands. They trust people they know. Meesho gave these women better tools to monetize trust that already existed.

Meesho doubled down on resellers: refined curation, streamlined suppliers, solved payments. They became infrastructure for India's informal women-led micro-businesses.

But resellers had natural limits. Even the best could serve maybe 50-100 people in their immediate network. To reach 500 million users, Meesho needed to evolve. How would they scale without losing what made resellers work?

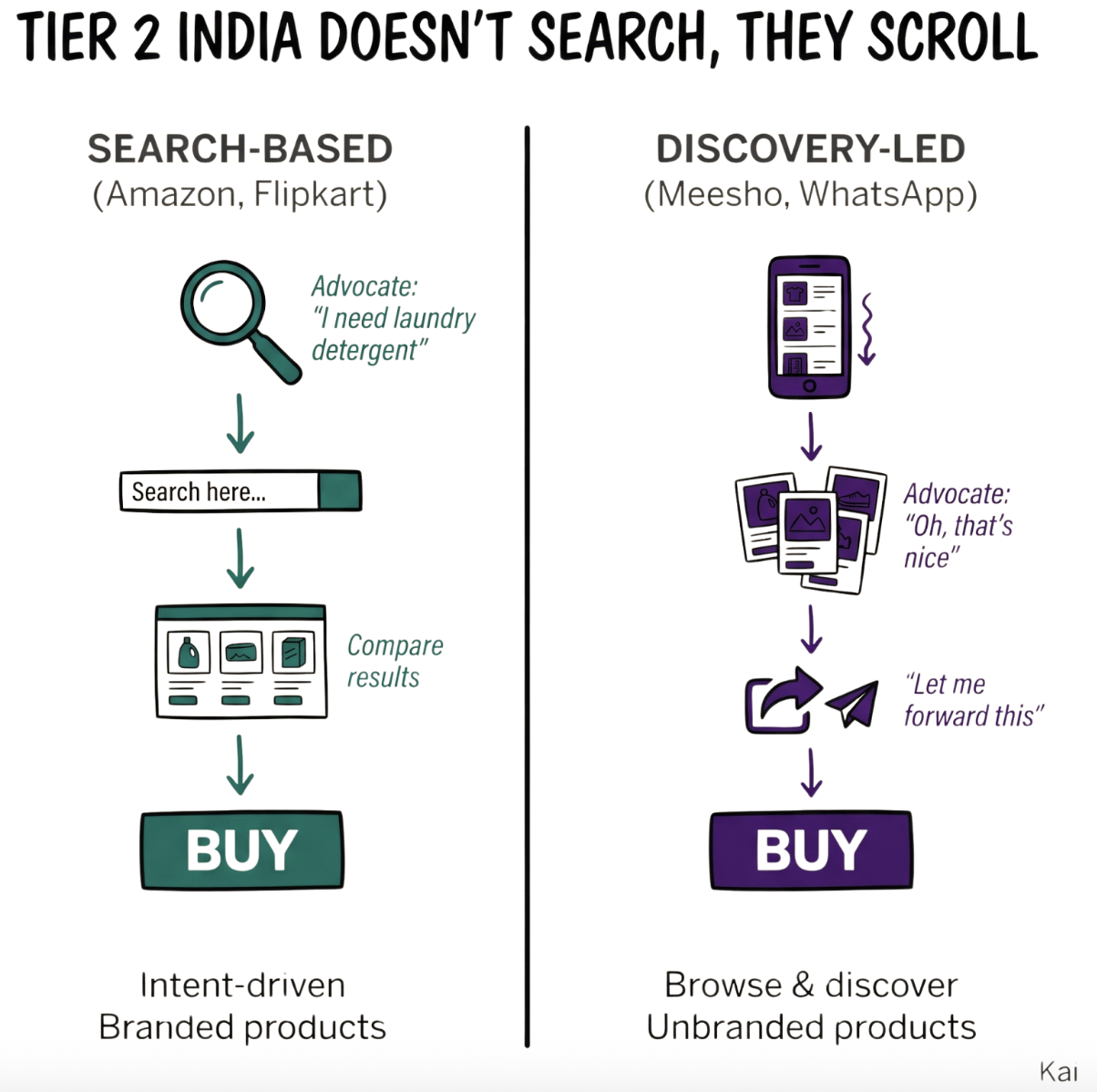

Insight 4: Tier 2 India doesn’t search, they scroll

Think about how you shop on Amazon: you have intent. You need laundry detergent, so you search "laundry detergent," compare options, read reviews, and buy. The entire interface is built around search.

Now in a WhatsApp group: you're not searching for anything specific. You're browsing. Sunita sent you 15 new product photos. You scroll through them. Oh, that's nice. Maybe I'll buy it. Oh, this would look good on my sister. Let me forward it to her.

This was really the only way product discovery could work for unbranded products. What keywords would you use for a $4 kurta with no brand? But you can browse, see something you like, and trust your own judgement about quality.

What Meesho Did: The move to a marketplace in 2021 was a recognition that the discovery behavior resellers had perfected (browsing, not searching) could be systematized at scale through algorithms. When they transitioned, they didn't build around search like Amazon or Flipkart; they kept the discovery-led shopping behaviour.

The app was built around scrolling through algorithmically curated feeds of products - more like browsing a bazaar than shopping in a store. Search is secondary. Just endless discovery.

The Lesson: Discovery-led commerce wasn't a stepping stone to "real" search-based shopping. It was the permanent model for unbranded products. Meesho preserved what made resellers successful - the browsing behavior - while removing their natural constraint of network size.

But going direct revealed that customers weren't just discovering differently. They were buying differently too. And that difference would become Meesho's most defensible moat.

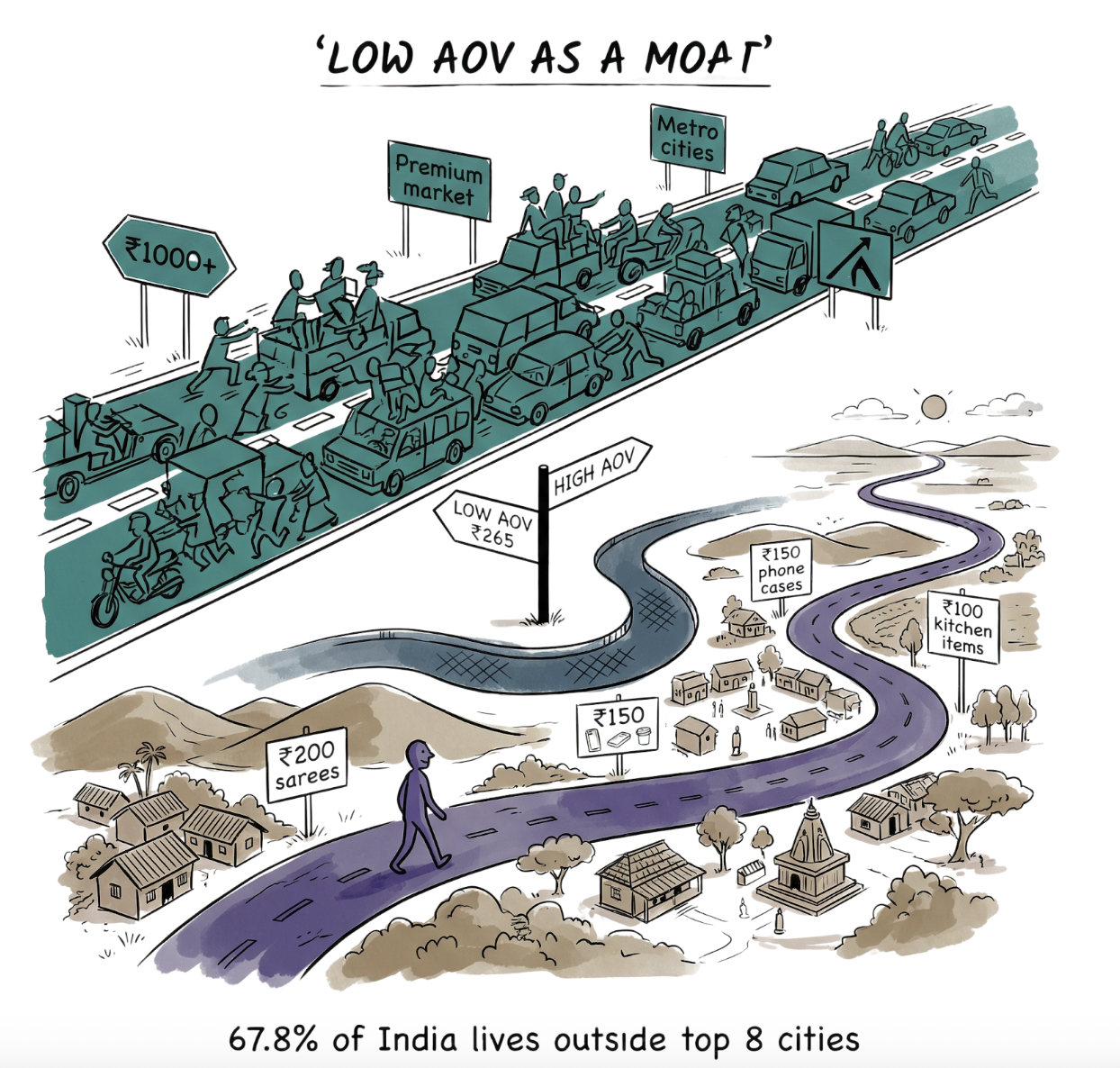

Insight 5: Low AOV can be a powerful moat (if your cost structure can support it!)

Conventional wisdom says low average order value (AOV) kills e-commerce economics. If Meesho charged 5% commission on a $3.60 order, sellers would lose money. Every e-commerce playbook says: increase AOVs or die.

Meesho went the opposite direction. They saw 87.8% of India living outside the top eight cities, buying ₹200 sarees and ₹150 phone cases. These customers want value over speed. They'll wait 20 days if the price is right.

Amazon and Flipkart cannot serve this market profitably. Their cost structures require higher AOVs. To compete at ₹265 average orders, they'd need to rebuild from scratch. Meesho's "weakness" became a moat competitors can't cross without destroying their existing business.

What Meesho Did: They launched a zero commission model to attract thousands of sellers with low-value, unbranded products that other platforms couldn't list profitably. Meesho's catalogue exploded with products that had no home elsewhere - the long tail of India's 70% unbranded retail. The algorithm we talked about above would support this: prioritise local suppliers where shipping costs can be a smaller share of the basket.

But zero commission only works if you make money elsewhere. Meesho had two revenue streams:

Advertising: With millions of sellers competing for visibility in those infinite scroll feeds, ad spend grew quickly. Sellers would pay to get their ₹200 kurtas shown higher in the feed.

Logistics fees: Sellers paid Meesho for shipping. If Meesho could fulfill deliveries cheaper than what sellers paid, they'd keep the margin.

The Lesson: Low AOV wasn't a bug to fix, but a moat around cost structure. It defined a market that competitors couldn't enter without fundamentally different unit economics. Advertising worked immediately, helping the platform showcase sellers to a large audience.

As for logistics, Meesho turned to the problem of profitable logistics at massive scale for tiny order values: the fragmented logistics landscape would become Meesho's advantage.

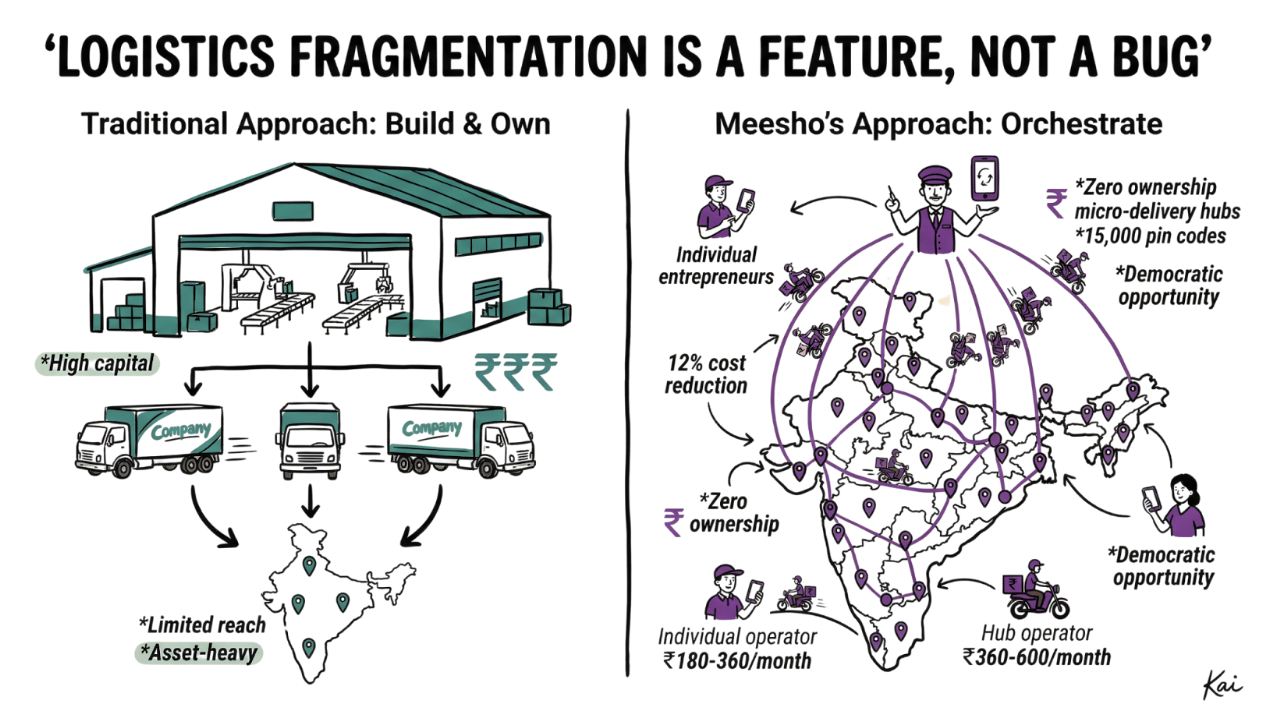

Insight 6: Vertical integration into logistics doesn’t require asset ownership

When Flipkart or Amazon ship an $18 product, a logistics cost of $0.60-0.96 is acceptable. But when you're shipping a $2.40 kurta to a remote town, that same logistics cost destroys unit economics entirely.

And Meesho needed to reach thousands of pin codes across India - many in rural areas where traditional logistics players had minimal or no presence. The obvious solution - building owned logistics infrastructure with warehouses and delivery fleets - would require massive capital expenditure and years to scale. It would also destroy the asset-light marketplace model that enabled Meesho's economics in the first place.

India's logistics landscape also presented a challenge: thousands of fragmented local operators, inconsistent quality, a lack of standardisation, and limited technology adoption. Every e-commerce player saw this fragmentation as something to overcome by building centralised infrastructure.

What Meesho Did: Instead of building logistics infrastructure, they built Valmo - an orchestration platform that coordinates between thousands of logistics partners across India.

Here's how it works: Valmo analyses each order - destination pin code, package weight, timing requirements, and available carriers in that region. Then it routes the order through the most efficient combination of local logistics partners, optimising for both cost and reliability in real-time.

The platform coordinates multi-stage logistics: first-mile pickup from sellers, linehaul transport between cities, and last-mile delivery to customers. Independent local operators manage each stage, but Valmo coordinates the handoffs seamlessly. Valmo is a conductor for a massive & distributed orchestra of local delivery operators.

Valmo's democratised logistics entrepreneurship. They created two distinct opportunity layers:

Individual delivery pilots can earn $180-360 monthly with just a smartphone and a two-wheeler. Zero investment required, flexible hours, working in their local area with no long commutes.

Delivery hub operators can build scalable logistics businesses with an investment of $1,200-2,400, earning $360-600 monthly by fulfilling orders. They coordinate logistics for their area - managing pickup from local sellers, sorting packages, and dispatching.

This model lets Meesho have a local presence in thousands of towns without building their own facilities, while creating sustainable businesses for entrepreneurs in Tier 2/3 cities where traditional logistics companies don't operate profitably.

By 2023, it was managing 22% of Meesho's orders. In 2024, that jumped to 62%. Coverage expanded to 15,000 pin codes - reaching towns and villages where traditional 3PL players couldn’t justify economics. And critically, Valmo reduced logistics costs by approximately 12% compared to using traditional 3PL partners exclusively. At Meesho's scale - processing 4.5 million daily orders - that 12% cost reduction translated to massive savings that made zero commission sustainable.

The same fragmented structure that made India "difficult" for e-commerce became Meesho's competitive moat.

The Lesson: Vertical integration doesn't require asset ownership. Orchestration at scale can be more powerful than infrastructure ownership, especially in fragmented markets. The same fragmented structure that made India "difficult" for e-commerce became Meesho's competitive moat. They enhanced the existing network of local logistics entrepreneurs rather than trying to replace them with centralised infrastructure - the same philosophy that made their reseller model successful, now applied to logistics.

–

As Meesho becomes a public company, they're proving that sustainable, massive businesses can be built by embracing India's complexity rather than trying to simplify it away.

Meesho's journey validates that India's most valuable companies will be built by those who respect its unique structure - low-trust, intermediary-dependent, permanently fragmented - rather than trying to force consolidation playbooks onto Indian markets.

Meesho's success validates a crucial insight: India's most valuable companies emerge from embracing its complexity rather than fighting it. But understanding the structure is only half the equation. The question that follows naturally is: what technological capability can finally make this fragmented, intermediary-dependent economy compete without losing what makes it work? That's where AI enters - not as a force for consolidation, but as the coordination layer India has always needed.