Open AI is now building…toys?

Ever since Jony Ive partnered with OpenAI to design what is rumored to be a heavily subsidised AI hardware device, Twitter has been buzzing with speculation about the future of AI hardware.

But why is the world's most advanced AI company, which has achieved unprecedented success with software, suddenly interested in building physical devices?

Today, when AI can clone software applications in minutes, building something defensible requires returning to the hard problems of atoms, not just bits. However, while Silicon Valley rushes to build AI-powered pins, glasses, and every conceivable connected device, there appears to be a misunderstanding about what consumers actually want from AI hardware. The graveyard of failed devices teaches us that tech adoption isn't just about what's futuristic; it's about what fits seamlessly into daily life.

What AI hardware has gotten wrong

A significant portion of AI hardware innovation today is misdirected. Many companies are designing products that cater to edge-case scenarios - those rare, 10% moments when users might need a futuristic digital assistant - instead of focusing on the 90% of interactions where people seek practical, contextual, and low-friction support. This misalignment explains why so many ambitious hardware projects fail spectacularly despite having cutting-edge tech and millions in funding behind them.

Take the Humane AI Pin – a $699 device that promised to liberate us from screens and usher in a post-smartphone era. Instead, it created entirely new frictions: awkward hand gestures, projected displays that were barely visible in sunlight, overheating issues that made the device uncomfortable to wear, and an AI that simply wasn't good enough to justify the cumbersome interaction model.

The device failed not because consumers weren't ready for AI, but because it ignored how phones have become extensions of ourselves. The Humane AI Pin asked users to learn an entirely new interaction paradigm for the promise of occasionally useful AI responses – a value proposition that simply didn't justify the friction.

The Humane AI Pin, Rabbit R1, and countless other devices share this fundamental flaw: they prioritise tech sophistication over utility, creating solutions in search of problems rather than addressing genuine pain points in people's daily lives.

But here’s what AI hardware could potentially get right

The path forward for AI hardware is not to replace existing behaviors, but to enhance them - invisibly, intuitively, and meaningfully. Successful AI hardware will be defined by its ability to integrate into familiar contexts and deliver incremental value that compounds over time, rather than by attempting to revolutionise user behavior from the outset, and we’re getting there.

OpenAI's recent partnership with Mattel is brilliant and represents a different approach to AI hardware. Instead of trying to replace phones or create new interaction paradigms, they're embedding AI into toys – a category where screens are actually unwanted and the value proposition is immediately clear. Parents actively seek alternatives to screen time for their children, and toys are natural vessels for AI companionship because they fit into existing play patterns. The genius lies in the invisibility of the technology; kids don't think about the AI, they just experience more engaging and personalised play. Companies like Curio have already shown this approach works. These products aren't trying to be everything to everyone; they're focused on one frequent and well-defined need: intelligent play that grows with the child.

In these scenarios, AI becomes a feature that enhances the core experience rather than the entire point of the product, which is why these devices succeed where broader AI hardware often fails.

The economics of AI hardware vs. software

As Naval observed, generative AI tools today can clone entire user interfaces in minutes. Software moats are increasingly temporary, and hardware moats, when established, can last for years or even decades because they involve supply chains, manufacturing expertise, and physical distribution networks that competitors can't easily replicate.

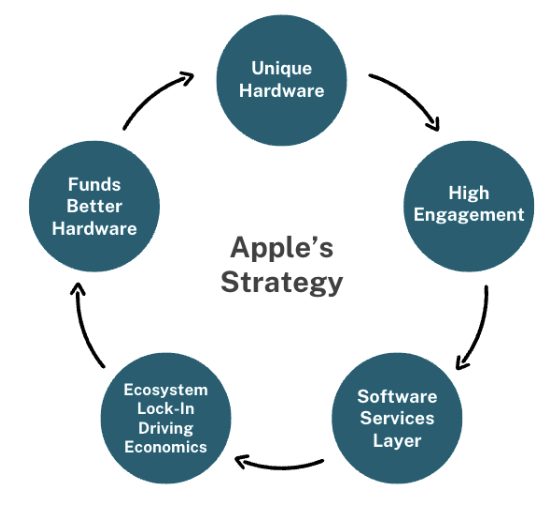

Apple exemplifies this strategy perfectly. The iPhone created a hardware moat through superior design and ecosystem lock-in that competitors still struggle to replicate nearly two decades later. But App Store commissions, iCloud subscriptions, Apple Music, and other software services now generate over $110 billion annually at margins approaching 70%. The hardware provided the defensible foundation, but software delivered the scalable economics that drive long-term value creation.

Similarly, AI-enhanced fitness equipment, cooking appliances, or productivity tools have the potential to work as they make familiar activities more effective rather than trying to replace them entirely. The key insight is that successful AI hardware amplifies human capabilities within existing contexts rather than trying to create entirely new categories of human-computer interaction.

This approach requires patience, market understanding, and recognition that the most defensible businesses often grow gradually rather than exploding overnight, but it also creates opportunities for genuine differentiation in an increasingly commoditised software landscape.